I Want to Become President to Make Slavery Legal Again Vine

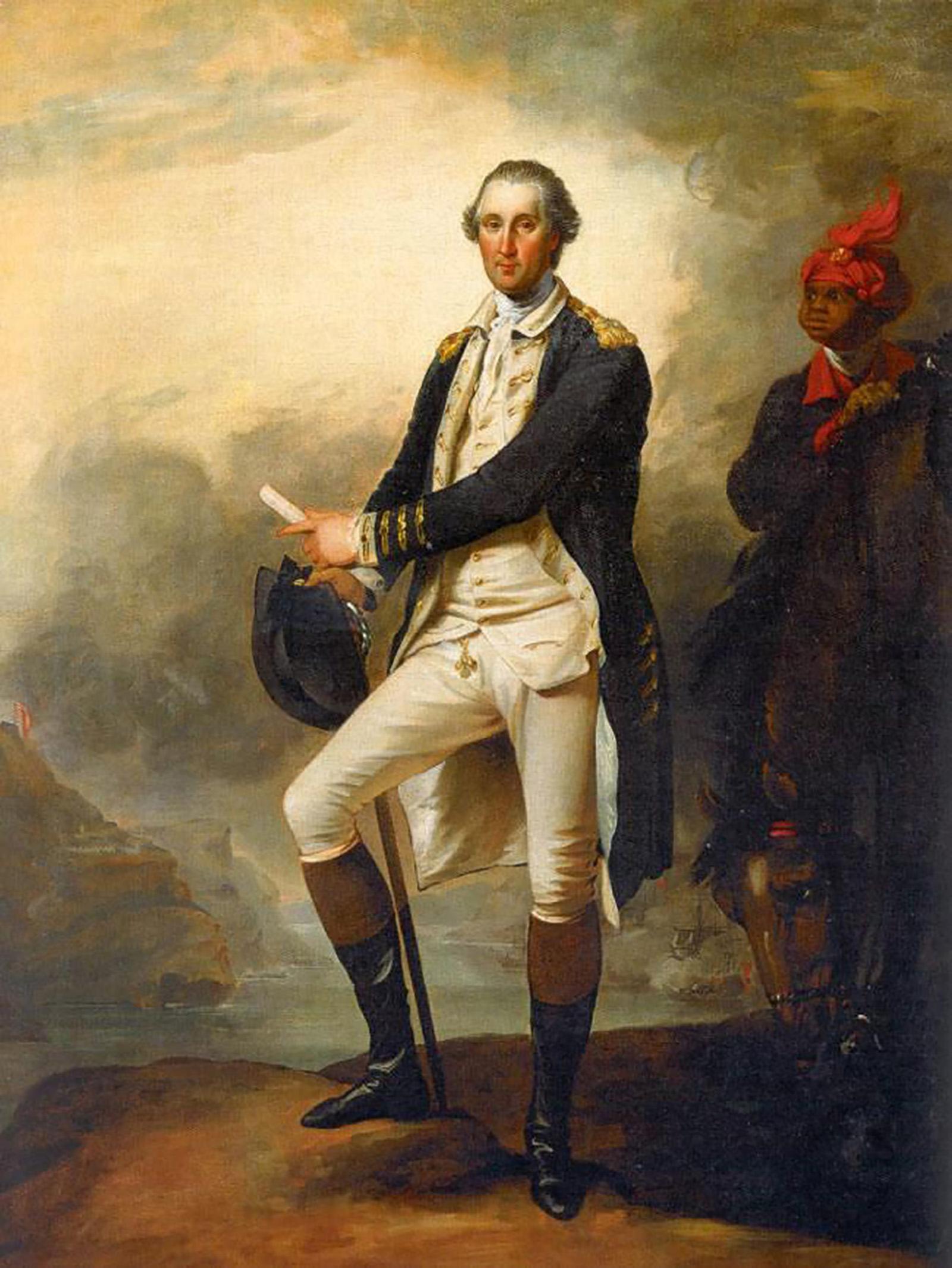

George Washington'southward views on the subject of slavery shifted over the course of his life. As a young boy, Washington grew upwardly in a guild that reinforced the notion that slavery was both right and natural. His parents and neighbors owned slaves. Past the fourth dimension of Washington'southward birth, slavery was an ingrained attribute of Virginia life for nearly a century and an indispensable function of the economical, social, legal, cultural, and political fabric of the colony. By the fourth dimension George Washington took control of the Mountain Vernon property in 1754, the population of Fairfax County was around 6,500 people, of whom a little more than than 1,800 or about 28% were slaves of African origin. The proportion of slaves in the population every bit a whole rose throughout the century; by the finish of the American Revolution, over 40% of the people living in Fairfax Canton were slaves.1

George Washington'southward views on the subject of slavery shifted over the course of his life. As a young boy, Washington grew upwardly in a guild that reinforced the notion that slavery was both right and natural. His parents and neighbors owned slaves. Past the fourth dimension of Washington'southward birth, slavery was an ingrained attribute of Virginia life for nearly a century and an indispensable function of the economical, social, legal, cultural, and political fabric of the colony. By the fourth dimension George Washington took control of the Mountain Vernon property in 1754, the population of Fairfax County was around 6,500 people, of whom a little more than than 1,800 or about 28% were slaves of African origin. The proportion of slaves in the population every bit a whole rose throughout the century; by the finish of the American Revolution, over 40% of the people living in Fairfax Canton were slaves.1

Early Experiences

George Washington became a slave owner at the early age of eleven, when his begetter died and left him the 280 acre farm near Fredericksburg, Virginia where the family was then living. In addition, Washington was willed x slaves. As a young adult, Washington purchased at least eight slaves, including a carpenter named Kitt who was acquired for £39.5. Washington purchases more than slaves in 1755, four other men, 2 women, and a child.

It was after his wedlock to Martha Dandridge Custis in January of 1759 that Washington'south slaveholdings increased dramatically. His young helpmate was the widow of a wealthy planter, Daniel Parke Custis, who died without a will in 1757; her share of the Custis manor brought another lxxx-iv slaves to Mountain Vernon. In the sixteen years between his marriage and the beginning of the American Revolution, Washington acquired slightly more than 40 additional slaves through purchase.ii Nearly of the subsequent increase in the slave population at Mountain Vernon occurred as a result of the large number of children born on the manor.

Slave Owner

Various sources offering differing insight into Washington'southward behavior every bit a slave owner. Richard Parkinson, an Englishman who lived about Mount Vernon, once reported that "it was the sense of all his [Washington's] neighbors that he treated [his slaves] with more severity than whatsoever other man."3

Conversely, a foreign company traveling in America one time recorded that George Washington dealt with his slaves "far more than humanely than do his swain citizens of Virginia." It was this human being's opinion that Virginians typically treated their slaves harshly, providing "only bread, water and blows."four

Washington himself one time criticized other large plantation owners, "who are non always as kind, and equally attentive to their [the slaves'] wants and usage equally they ought to exist."5 Toward the end of his life, he looked back on his years every bit a slave owner, reflecting that: "The unfortunate condition of the persons, whose labour in part I employed, has been the but unavoidable subject of regret. To brand the Adults amongst them equally easy & as comfy in their circumstances as their actual state of ignorance & improvidence would acknowledge; & to lay a foundation to ready the ascent generation for a destiny unlike from that in which they were born; afforded some satisfaction to my mind, & could not I hoped be displeasing to the justice of the Creator."vi

Changing Views

Over the form of Washington'due south life, he gradually inverse from a young human who accustomed slavery as thing of form, into a person who decided never once more to buy or sell another slave and held hopes for the eventual abolition of the institution. Probably the biggest factor in the evolution of these views was the Revolutionary War in which Washington risked his life, his family, a sizable fortune, and a stable future for freedom from England and some idealistic concepts about the rights of human. During the conflict, his views on slavery were radically altered. Within three years of the kickoff of the war, Washington, who was then forty-six years old and had been a slave possessor for thirty-v years, confided to a cousin that he longed "every day...more and more to get clear" of the ownership of slaves.7

During the state of war Washington traveled to parts of the land where agronomics was undertaken without the apply of slaves. He also witnessed black soldiers in action, fighting bravely in the Continental Army. Within seven months of taking control of the regular army, Washington approved the enlistment of costless black soldiers, which he and the other full general officers had originally opposed.8

It was also during the state of war that Washington was first exposed to the views of the Marquis de Lafayette, who ardently opposed slavery. During the period between the end of the war and the start of his presidency, abolitionists began approaching Washington, seeking his support for their cause. Over and over again, he responded with his conviction that the best way to effect the elimination of slavery was through the legislature, which he hoped would set up a program of gradual emancipation, and for which he would gladly give his vote.

Every bit he wrote to his friend Robert Morris in 1786, Washington hoped that no one would read his opposition to the methods of sure abolitionists, in this example the Quakers, as opposition to abolition as a concept: "I hope it volition not be conceived from these observations, that it is my wish to agree the unhappy people, who are the subject area of this letter, in slavery. I can just say that at that place is not a human living who wishes more sincerely than I exercise, to see a program adopted for the abolition of it; but in that location is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that is by Legislative dominance; and this, as far as my suffrage volition become, shall never be wanting."9

Washington admitted to Lafayette, however, that he "despaired" of seeing an abolitionist spirit sweep the country. He confided to the younger homo in 1786 that "some petitions were presented to the Associates at its last Session, for the abolitionism of slavery, but they could scarcely obtain a reading. To set them [the slaves] adrift at once would, I really believe, be productive of much inconvenience & mischief; simply by degrees it certainly might, & assuredly ought to be effected & that besides past Legislative authority."x

George Washington's Will

While he never publicly led the effort to cancel slavery, Washington did endeavour to atomic number 82 past setting an example. In his will, written several months before his decease in December 1799, Washington left directions for the emancipation after Martha Washington's death, of all the slaves who belonged to him. Washington was non the merely Virginian to free his slaves at this period. Toward the stop of the American Revolution, in 1782, the Virginia legislature made it legal for masters to manumit their slaves, without a special action of the governor and council, which had been necessary before.

While he never publicly led the effort to cancel slavery, Washington did endeavour to atomic number 82 past setting an example. In his will, written several months before his decease in December 1799, Washington left directions for the emancipation after Martha Washington's death, of all the slaves who belonged to him. Washington was non the merely Virginian to free his slaves at this period. Toward the stop of the American Revolution, in 1782, the Virginia legislature made it legal for masters to manumit their slaves, without a special action of the governor and council, which had been necessary before.

Of the 317 slaves at Mount Vernon in 1799, a fiddling less than half, 123 individuals, belonged to George Washington and were set gratuitous nether the terms of his will. When Martha Washington'due south first husband, Daniel Parke Custis, died without a will, she received a life interest in one-third of his estate, including the slaves. The other two-thirds of the estate went to their children. Neither George nor Martha Washington could free these slaves past law and, upon her death they reverted to the Custis estate and were divided among her grandchildren. By 1799, 153 slaves at Mount Vernon were part of this dower holding.

In accordance with state law, George Washington stipulated in his will that elderly slaves or those who were likewise ill to work were to be supported throughout their lives by his estate. Children without parents, or those whose families were too poor or indifferent to see to their education, were to be bound out to masters and mistresses who would teach them reading, writing, and a useful trade, until they were ultimately freed at the age of 20-five.11 In December 1800, Martha Washington signed a deed of manumission for her deceased husband'south slaves, a transaction which is recorded in the abstracts of the Fairfax County, Virginia, Court Records. The slaves would finally receive their freedom on January one, 1801.12

Mary Five. Thompson

Inquiry Historian

Mount Vernon Estate and Gardens

Notes:

1. Donald One thousand. Sweig, "Slavery in Fairfax Canton, Virginia, 1750-1860: A Research Report," (Fairfax County, Virginia: History and Archæology Section, Office of Comprehensive Planning, June 1983), 4, 8, fifteen.

2. Wills of George Washington and His Firsthand Ancestors, ed. Worthington Chauncey Ford (Brooklyn, New York: Historical Printing Society, 1891), 42 and 42n; Worthington Chauncey Ford, Washington as an Employer and Importer of Labor (Brooklyn, New York: Privately Printed, 1889); "Worthy Partner": The Papers of Martha Washington, ed. Joseph E. Fields (Westport, Connecticut and London: Greenwood Press, 1994), 105-107.

three. Richard Parkinson, A Tour in America, in 1798, 1799, and 1800 (London: Printed for J. Harding and J. Murray, 1805), 420.

4. Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Under Their Vine and Fig Tree: Travels through America in 1797-1799, 1805, with some further account of life in New Jersey, ed. Metchie J.E. Budka (Elizabeth, New Jersey: The Grassman Publishing Company, Inc., 1965), 101.

five. "George Washington to Arthur Young, eighteen June - 21 June 1792," ed. John C. Fitzpatrick, The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources 1745-1799, Vol. 32 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1931), 65.

6. David Humphreys, Life of George Washington with George Washington'due south Remarks, ed. Rosemarie Zagarri (Athens: Academy of Georgia Printing, 1991), 78.

vii. "George Washington to Lund Washington, 15 August 1778," The Writings of George Washington, Vol. 12, 327.

8. George Washington, "Full general Orders, 31 Oct 1775 and 12 November 1775," The Writings of George Washington, Vol. 4, 57 & 86. Run into too The Writings of George Washington, Vol. 4, 8n.

9. "George Washington to Robert Morris, 12 April 1786."

10. "George Washington to the Marquis de Lafayette, ten May 1786," The Papers of George Washington, Confederation Serial, Vol. four, 43-4.

eleven. The Statutes at Large; Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, From the First Session of the Legislature, in the Yr 1619, Vol. half-dozen, ed. William Waller Hening (Richmond, Virginia: Printed for the editor at the Franklin Printing, 1819), 112, and Vol. 11 (Richmond, Virginia: Printed for the editor by George Cochran, 1823), 39-40.

12. The Last Will and Testament of George Washington and the Schedule of Holding: to which is appended the terminal volition and testament of Martha Washington. sixth ed. rev., ed. John C. Fitzpatrick (Mountain Vernon, VA : Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union, 1992), ii-4. For Virginia laws dealing with the estate bug and manumission requirements faced by the Washingtons, see The Statutes at Large, Book V, ed. William Waller Hening (Richmond, Virginia: Printed for the editor at the Franklin Press, 1819), 445, 446, and 464; Volume Eleven (Richmond, Virginia: Printed for the editor by George Cochran, 1823), 29-40; Volume XII (Richmond, Virginia: Printed for the editor past George Cochran, 1823), 145, 146, and 150.

copplesonconat1951.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/george-washington-and-slavery/

0 Response to "I Want to Become President to Make Slavery Legal Again Vine"

Post a Comment